Hite, like many Utah towns, was founded by an enterprising prospector. Cass Hite came to Glen Canyon in the 1880s in search of gold and when he found it, a small gold rush ensued. The boom didn’t last long but a town named for Hite grew there nonetheless. Hite was located on an easily navigable part of the Colorado, a river that had few opportunities for safe crossing. After the gold rush bust, there was a uranium boom and many people came to the area. A man named Arthur Chaffin built a ferry that brought people and their cars across the river, one or two at a time. Over the years, Chaffin helped build roads and bridges in the area, opening a scenic part of Utah to automobile traffic. He was a man of determination and saw an opportunity for tourism. One source tells how, in 1932, Chaffin borrowed a bulldozer from the Utah Highway Department and carved a road into the steep rocks and canyons, forging a connection between his place and the outer world. The enterprising ferryman opened a tent motel and a post office which made up the town’s entirety. Hite developed into a small riverside oasis, famous for its fruit trees and melons, until 1964 when the town was submerged as Lake Powell filled.

One of my happiest childhood memories is from a multifamily vacation at Lake Powell. It was the summer of 1992 and four families from church drove out across the desert to rent two houseboats and a speed boat for skiing. There were eight adults and nine kids and even though we outnumbered them, I think it was the adults who had the most fun. The adults really let loose; they performed monologues and heroic feats and, because we were church folks, we knew all the same songs and so there was constant singing and a lot of laughter. I’ll never forget how one mother water-skied topless. Later, she triumphantly stirred the boat’s toilet with a stick so there was room for the remaining days of many people’s poop. I remember floating in an inner tube for hours until the adults finally allowed us to swim back to the boats.

I grew up with these people, not just the kids but especially the adults who were our choir directors and trip leaders and bible school organizers. All of these folks, including my parents, worked together to run the church’s community theater group. Of the extended family that was First United Methodist Church, these were the core favorites. I saw these people as many as three times a week for nearly the entirety of my growing up but never before had we busted out like this. Though I’d spent years of my life in these people’s homes, not to mention on choir tours and mission trips and our church’s “high adventure” camping excursions, this was different. At Lake Powell, we found ourselves floating and motoring through a completely new world without an agenda, nothing to practice, no necessary prayers. We were dear friends bound by something that transcended a building or an ideology, something that held up despite the busted boat motor or a night without beer.

The Colorado River is big and mighty. It trickles out of the Rocky Mountains and gathers force as it splashes and gurgles across the arid southwest. It carves out the Grand Canyon and the Colorado Plateau and winds its way south to the Sea of Cortez. Before it was dammed in two places, becoming the water source for 40 million people, it was unpredictable, ferocious, shaping the earth in magnificent ways. The River’s 1450-mile journey begins in the highest of mountains, traveling through tundra, tumbling down cliff walls and crashing through stone to emerge in the driest and hottest of deserts where the river spits bits of sand into a place unimaginable from the river’s alpine headwaters. The drainage basin or watershed of the Colorado River encompasses 246,000 square miles, an area that touches seven US states and two in Mexico. So many streams and creeks flow into it: the Dolores, the Roaring Fork, the Gunnison, San Juan, Virgin, Gila, Salt, and the Green. For centuries, Native people lived along this river basin, migrating with the seasons, the floods and droughts. But when European settlers came west, they wanted to build towns that were irrigated but safe from flood. They figured out how to move water to where it hadn’t gone before. With waterworks, more people could settle the arid lands and with more people capable of such labor, those mammoth feats were actually possible. And so development boomed. The 20th century was a flurry of construction and engineering that introduced new pipelines and culverts and channels, troughs, tunnels, aqueducts, conduits, ditches, tubes and diversions.

In 1900, one such diversion was built in the Imperial Valley to provide farms with water from the nearby Colorado River. Historically, the river flooded various parts of southern California. Silt and soil was deposited by the river, causing its delta to move back and forth across the land like the tail of a lizard skittering over hot rocks. But people found it hard to build their lives on a floodplain; the water had to be moved. A few years after the diversion was built, it got clogged and the attempts to remedy the clog failed. So in 1905, the river flooded into the landlocked Salton Basin, creating a lake. It wasn’t so bad at first. Birds came to nest, farmers flourished, and a resort town was built on the new inland Salton Sea. But by the 1970s, the lake shrunk and with the run-off from local farms, the water turned to poison. Huge numbers of birds and fish died, scattering the shore with their toxic bodies. Because of this ugly sight and the intensifying stench, tourists stopped coming. By 1999, the waters receded so much that whatever had flowed into the lake from nearby farms was now exposed to air. It dried up and blew around, filling the neighboring communities with toxic dust. The Salton Sea has been called the greatest environmental disaster in California history with millions of dollars recently allocated to its remediation.

Long before the Imperial Valley got sick on its own shit, people wanted the Colorado dammed. It was too erratic, too unpredictable; if not subjugated it might destroy all that the west could become. Between 1931 and 1936, Hoover Dam was built in the Colorado’s Black Canyon. But the water and power supplied by the new dam wasn’t enough for the growing population; plus the raging resource clearly had more life to give. So in the 1950s, the Bureau of Land Management acquired the site most desirable for a new dam and reservoir by negotiating a land swap with the Navajo Nation who ceded Glen Canyon in exchange for the return of stolen sacred land elsewhere in the region.

I watched a film about the Glen Canyon Dam that was made during the time of its construction. It is the mid-1960s, so the narrator wears a dark suit and smokes in front of the camera and speaks in that crooning voice that gently booms with authority. The film opens with dynamite, a massive canyon wall is seen exploding from aerial view. From way up there, the narrator’s voice proclaims the river “a monster” and “a thing to be tamed.” In the next scene there are giant earth movers and more explosions.

We learn that roads had to be built to reach the canyon’s rim, then a bridge to cross it. Within moments, cranes hoist equipment in and out of the 700-foot canyon while a fleet of never-ending trucks carry dirt from the bottom to the top; heroes in hard hats swarm everywhere. A company town is built to support the workers who number in the thousands. In order to build this massive dam, the monstrous Colorado must be diverted and so two giant tunnels are engineered to change the river’s course with hyper-meticulous control.

While the waters are being manipulated around the dam site, a huge concrete plant is installed nearby. Cableways taught between movable towers span the canyon, from which buckets of concrete swing over the chasm and carefully pour into tall wooden forms. Construction starts at the bottom of the canyon and, as the concrete dries, the forms and equipment are moved higher and higher. Eventually it is done. A little over ten years after the first explosion, the dam is celebrated in a public dedication. The story concludes with a Navajo marching band playing the national anthem from atop the bridge. Lady Bird Johnson addresses a crowd of 30,000. The narrator’s voice swells with the final phrases of music, welcoming progress to the west and the wide world beyond.

In the end Glen Canyon Dam cost $187 million to build. It was 710 feet tall and contained 4,901,000 cubic feet of concrete. By my calculation, that means the dam weighs half a billion pounds. When all that weight was amassed and shaped but before the last layer dried, water was allowed back into the canyon and began filling up behind the dam. Glen Canyon was chosen for a reservoir because it could hold an immense amount of water. It’s so big that it took over 17 years to fill; in 1980, it finally hit capacity. When full, Lake Powell is 180 miles long with 1,960 miles of shoreline. Its volume holds 6 million acre feet of water. Now, an acre foot is about 326,000 gallons of water; that’s enough water to cover a football field in a foot of water. When I try to calculate the weight of 6 million acre feet of water, my calculator nearly breaks. It’s over 16 quadrillion pounds or 8 trillion tons.

Someone must’ve spent a lot of time in Glen Canyon with maps and measuring devices and doing fancy math. All kinds of equations went into figuring how the reservoir might fill, to what level, and then how the dam might be managed due to fluctuations in rainfall, snow melt, and evaporation. You see, a dam is more than a big fat wedge that seamlessly holds back the flow of water. Its primary function is one of control, releasing calculated amounts of water at specific times. Ideally, it’s designed to maintain some kind of balance because the rivers and reservoirs downstream are each impacted by the dam’s levels and the river’s flow. The dam requires man to take control, to maintain control, it puts man in the god seat. And you can hear this in the film narrator’s voice — a fist-pumping, flag-waving, river-suppressing pride.

I wonder if there was fist-pumping in Hite when the lake came to engulf the town. Hite is at the north end of Lake Powell and so when the water backed up behind Glen Canyon Dam, it was one of the last places to fill in. Arthur Chaffin was an engineer and a roadbuilder, a steward of progress. He and the Hiteites must’ve known their town would drown but what’s it like to watch your orchards and tent camps go underwater? It’s hard to find information about Hite on June 5, 1964 and what little I’ve found makes it sound like Hite just flooded, filled up, washed away. But you just have to wonder: did the water come suddenly or did it creep over days? Who was watching? What was the feeling in the air? Does a thing like that make you hate lakes? Arthur Chaffin, of course, lost everything in the flood and after successfully suing the federal government, he moved elsewhere with $8,000. But that’s all I know. $8,000. How did that feel?

…

Something like duty pulls me to places like Hite. I’m fascinated by sites of exploitation and extraction, as if bearing witness can somehow fix it, as if seeing it for myself in real time and space can somehow breach the soundbites and google searches to color in the gaps. I’m interested too in the quiet mysterious places and I search for the palimpsest that time leaves on a place, the traces and non-traces, the things seen by those who remember or know. Most of what has ever happened is invisible — it’s dead and gone — but I like the way my imagination gets sparked when I ask myself to imagine something about the place I’m in, something that history suggests but isn’t apparent. By learning to see things invisible or forgotten, I’m training my night vision to better navigate in the dark. It’s a form of ghost hunting, really.

To reach Hite, I travel down from the north on the road that Arthur Chaffin made. It is a beautiful road lined with canyons of white and red rocks. I stop at a scenic pullout, high above the river. I eavesdrop on a bunch of bikers comparing notes about biker apps. From above, the river looks small and timid. It is a hot May day and the Colorado’s iconic red earth appears in high contrast to the shocking new green that smudges the river’s marshy curves. I peer into the heat, scanning the wide canyon bottom for signs of the lake. Back in the van, I check the map to confirm Hite’s location.

In the 21st century, we don’t doubt maps. In fact, we don’t even need maps to know where we are. Our phones know direction and terrain better than we do; we just have to follow instructions and maintain a constant signal. But I’m a map lover and a luddite and I know how patchy cell service can be in these parts so I’m using my atlas to navigate. My 64-page DeLorme Gazetteer features oversized maps of Utah’s every inch. It shows roads and landmarks, topographic features, place names, campgrounds, towns, historic sites, creeks, peaks, lakes. It has different color codes for private land versus public land; it names the recreation areas and national parks and military bases and Indian reservations. On page 53, Lake Powell is like a blue centipede scrawled across a quarter of the page, its long tail wiggling north. In this map, copyrighted in 2019, Hite is touched by blue. And so when I come down off the cliffs and cross the river over two grand bridges and follow the signs to Hite where a campground and a dock and a visitors center were built at the lake’s edge, a horror comes over me.

I’m not sure what I expected to find - an underwater post office? A dock full of boats? Some sunburnt and singing church folk let loose on vacation? I anticipated looking at the lake while imagining what had been there before but I had not anticipated looking for a lake that no longer existed. The maps have lied. The water is gone.

I park the van and, because there is no shade, I stop in the blazing hot glare of noonday sun. I pull on the door of a closed ranger station and then step across the blistering parking lot to find the bathrooms similarly locked. Beneath the lip of a slight overhang, I examine the now-dated parks service signs where figures on water skis fade into a white glare. In the sudden heat, I feel mocked by this deceptive lake. All that remains is dry cracked earth. The pavement fractures and heaves; it is quickly too hot to walk.

Back in the van, I give thanks for the roof’s cover as I cruise slowly through the recreation area’s abandonment. There is a campground evenly arranged upon the land, each with a picnic table and a tent site and a hooked pole from which to hang caught fish. There are picnic areas too with iron BBQ grills that, in their overexposure, feel both ironic and sad. The place blazes and blinds. It is a hell place, a ruined place, a place that no one might ever come again. I drive down the boat ramp until it docks into red dirt.

Here was the bottom of the lake. Here was a once-drowned town. Here was a place where kids jumped into the water, parents warning to stay clear of the motor boats. Here is where fish were thrown back after the day’s catch was made but the fun wasn’t yet over. Here was the flood plain of a river before it was dammed.

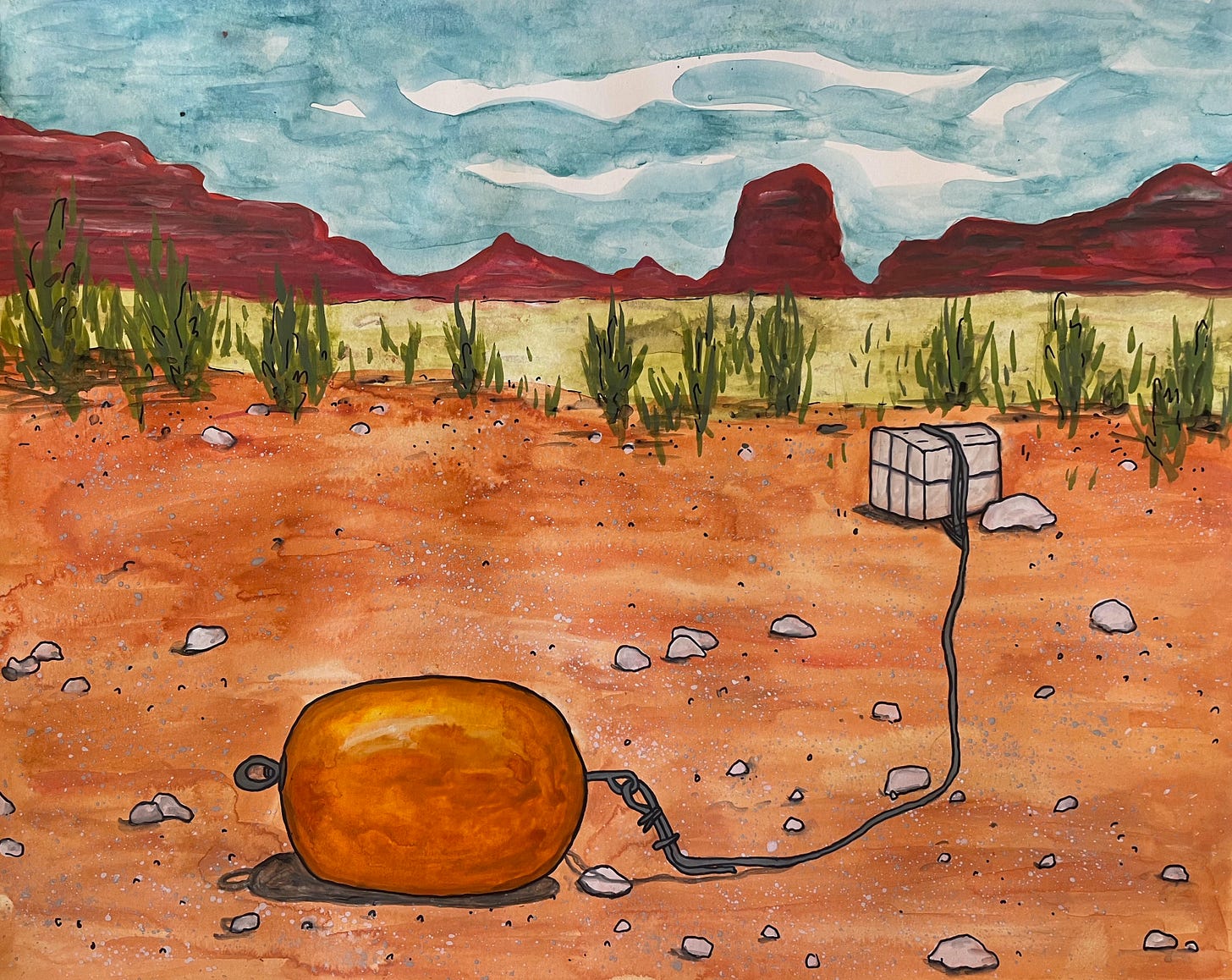

I step onto red earth and walk among new sage brush and bright tamarisk. I find an orange buoy still leashed to a giant concrete anchor. A narrow dock is cast aside, sunk, discarded on the shore of this dirt. I feel humiliated for these ridiculous objects, languishing in the pathetic dust. They groan with abandonment and, through the heat’s mirage, they shout a lesson about obsolescence and waste. This is a landscape burned with muted failure. Was it worth it? the bouy taunts haughtily. Was it worth it? The dock echoes hotly. I cannot answer; the heat has sucked every explanation from my mouth. I leave quickly, run out by the blame of dead objects. Back on the highway, a confused shame — is it mine or someone else’s? — drags behind me like a blocky concrete anchor.

…

When my parents split up, I was 15. I remember that I was sitting in the living room making mix tapes on the family stereo when we were called together for an important talk. The news of their break-up was so surprising that I didn’t even cry. My parents never fought and our family seemed happy. I couldn’t make sense of it and busied myself with the stops and starts of my recording project.

When my parents split up, no one else could believe it either. So no one really talked about it. It was confusing; it made no sense. Our entire world was made up of families just like ours - white, Christian, happy - and none of them split up. I understand now that my parents’ divorce felt so surprising because the rupture came from far below the surface; it was tectonic, geologic, not visible to the naked eye. The long-term wear of their disconnection was not disastrous but it rubbed them to the point of exhaustion. We were all constantly exhausted living the American dream, running from school to choir practice to dance class to forensics to swim meets to youth group to play rehearsal and finally to bed. Ours was a privilege of constant extracurricular activity, made possible by the fortitude and teamwork of middle class nuclear families. When my parents split up, no one asked very many questions; they just got busy doing something else. We all kept singing in the choir but we didn’t hang out afterwards anymore. Our family’s break up made a long low rumble that darkly echoed through the church’s halls.

I’ve never really understood why the church families didn’t crowd around my parents and dowse them in love. Instead, it seemed the four of us were left to drift off; we didn’t know we’d been untethered and drifting until there was no way to get back and by that point we may not have even tried. It’s been decades since I’ve seen the folks from our Lake Powell trip. The adults are getting old now and almost all the kids have kids of their own. It’s stunning to think that people can be family for more than a decade of your life and then, in no time at all, they become distant strangers. It’s kind of like a great big lake that one day dries up. While you were busy doing everything else, the water suddenly receded from the place you built your dock.

For so many reasons, Lake Powell is a tragedy. The Glen Canyon Dam was built during an era when rain and snow fell more abundantly across the Southwest and it banked on there being a similar future. But the region has grown more arid and is 20 years deep into a serious drought with climate change affecting every estimation of what might become normal. In a place with such high temperatures and walls of solid rock, the lake loses 50 inches or 690,560 acre-feet of water each year to evaporation. In fact, it has only been filled to capacity once — in 1983 — and has never been full again. Now, the lake sits at 35% and is shrinking still. Every year, the lake loses more water than it gains. Some call Lake Powell a “dead pool” because its levels have dropped so low that it’s essentially unusable.

I flee the non-lake, flooded with memories and sorrows. I think about my childhood reverie, the hours of diving and floating, how surely the lake and I swapped parts of ourselves. In this way, Lake Powell feels a bit like my lake, because I knew it once — intimately, joyfully, with all of the trust and wonder that is childhood vacation. But what stake can I possibly have in this lake, in this river? Am I entitled to its quenching waters? And am I responsible for its dead pools and bad dams? I try to apologize to this place but in the echoing silence, I’m reminded that places don’t forgive. They just keep changing.

Before the dam, Glen Canyon was a wonderland of gorges, spires, cliffs, and grottoes; it was the biological heart of the Colorado River, with more than 79 species of plants, 189 species of birds, and 34 species of mammals. It was also a cultural treasure with more than 3,000 ancient ruins. As the lake dries up, landforms are reemerging from the waters, hinting at the wonders of the deep. Many people are calling for the lake to be drained and the dam removed.

What will be revealed if the lake is drained after all? Will the Hite post office finally appear? I imagine the canyons will reemerge, coated in dead fish and plastic bottles and the deteriorating remains of so many summer vacations. Lake muck will dry up and blow around but the water lines will probably stay. The maps will need to be redrawn.

Hite reminds me that things are never as they appear; they certainly don’t go as planned. Whether you come away with $8,000 or divorced parents or a hell-scape of a campground, it’s hard to know what you have until it’s too late. And yet something miraculous is always emerging from the deep. Something is always changing.

I roll down the window and shriek into the wind as I keep on moving down the road.

Questions for readers and place explorers:

Where do you witness the palimpsest of history? Are there places within your landscape that have changed dramatically during the course of your life? I’d love to hear your thoughts about the markers and makers of those changes.

As I wrote this essay, it was fun to think about adult joy from a child’s point of view. I wonder if there are places in your memory where you witnessed your parents relaxed and happy? I think we might need a few more of these stories in circulation!

Do you think that Lake Powell should be drained?

How did you do with the longer read? Should I keep it shorter for shorter attention spans? These things take time and labor, so let me know what’s working for you!

Side note: this essay is the 11th chapter in my in-progress manuscript that documents my COVID-era travels through Utah; it’s called Into the Folding Swell. Stay tuned for news about its publication!

Oh, my gosh. This post was fascinating and VERY POWERFUL! Thank you, Erin.